The agreement on climate change, reached in Paris on 12 December, was momentous for reasons beyond the obvious. The world watched the two weeks of negotiations at COP21 (Conference of Parties) eagerly, hoping for a strong and definitive agreement to mitigate and adapt to climate change and develop a road map for securing the means by which these targets could be achieved. However, there were several tense moments, with India often in the thick of things, which suggested that the hope for such an agreement might have been too optimistic or misguided.

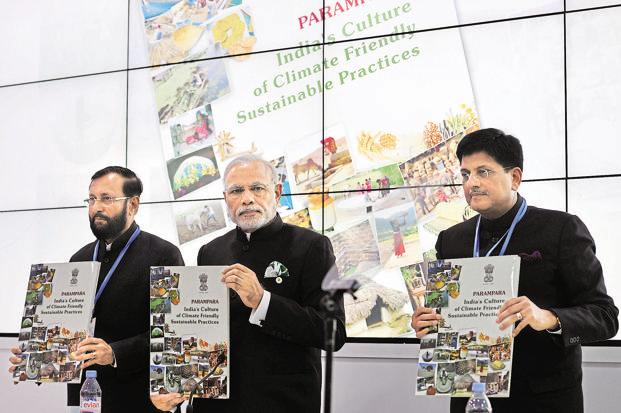

For there to be a climate deal, one that Prime Minister Narendra Modi calls a victory for climate justice—a concept heralded by India as central to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s principles—is indicative of India’s front-line role in influencing the text, tone and spirit of the Paris agreement.

To understand whether India has gained or lost from this deal, the reference to a context is critically important. The most recent and relevant context is the Bonn context. The Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (ADP) meeting in Bonn, came up with the initial text five weeks before COP21, with much of it in square brackets, clearly showing the lack of agreement on almost every major topic.

One major point of discord was an attempt by the US to discard the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR). US secretary of state John Kerry’s statement that India will be a challenge at the Paris summit was clearly an attempt at putting pressure on the country. While the negotiations were underway in Paris, The New York Times published a cartoon with an elephant labelled India obstructing the Paris climate summit train, mocking India’s stand at the negotiations.

Undeterred by the pressure, CBDR, a tenet central to the UNFCCC charter, was defended valiantly by India with support from other like-minded developing countries. While the agreement has responsibilities for all nations, India was able to get the agreement to retain the principle of CBDR in the key elements of technology transfer, finance, adaptation and capacity building.

The second context is the Kyoto context. Kyoto Protocol, the contentious 1997 agreement, pinned the responsibilities of deep mitigation as well as financial support on developed countries alone, with developing countries, like India, taking all climate mitigation actions contingent on receiving financial and technological support. The Paris agreement, if viewed from this perspective, is a loss for India. In all probability, given past failures of developed countries to meet their obligations, finance and technology will not be forthcoming for all domestic mitigation actions.

However, India realizes that the global economy, energy markets and climate science have come a long way since 1997. Further, India, along with most countries of the world, wanted the Paris agreement to have a scope much broader than the Kyoto Protocol. As a result, India played a constructive role in arguing for ambitious commitments on finance (a floor under of $100 billion), capacity building (including for monitoring and reporting) and technology support (including partnerships) from developed to developing countries, without being obstructionist as it was often wrongly accused of being.

The deal in effect has given India something in between the Kyoto perspective and the Bonn perspective. India has done well to defend its development priorities, while detailing its ambitious renewable energy targets. The path-changing outcome of the deal is that it is going to change the state of global markets, decidedly away from long-term investment in fossil fuels. The rate of decline in energy technology costs will fundamentally determine how the world actually ramps up mitigation effort.

India has positioned itself as a leader in the renewable energy space by spearheading the creation of the International Solar Alliance (ISA). ISA, through the principle of demand aggregation, could potentially lead to significant further decline in solar technology costs, as multiple countries come together for scaling global solar power production. This is what India did domestically with the hugely successful LED procurement and distribution programme. It is only through market interventions like these that the costs of mitigation technologies could be lowered globally, making mitigation actions relatively easier, as well as lowering the need for supporting finance from the developed world.

Further, the progressive monitoring of actions by the developed world as well as the scaling up of commitments (which are optional for developing countries) provide a lever for India and other developing countries to hold the developed world accountable, compelling them to do more than they have done so far. The developed countries have no more excuses left for their lack of ambition or action. Monitoring of actions by countries, a clause that does not include differentiation, is beneficial at its best and redundant at its worst, as countries already submit national communications of their emissions. It remains to be seen if the national action monitoring will result in increased actions on the ground—this will be the determining factor of the impact of the Paris agreement.

Give and take in international negotiations is imperative, and what India has managed to achieve at Paris, in text and in actions beyond the text, is commendable. What India really needs to ensure is that it alters the mitigation debate from challenges to opportunities. India would do well to grab the opportunities for developing domestic solar panel manufacturing industries, energy storage solutions, grid integration solutions, electric vehicles, battery manufacturing facilities and building a skilled renewable energy workforce. All of these initiatives would be both essential and spurred by India’s domestic priorities of Make in India, the 175GW renewable energy target and the 24×7 electricity for all target.